House History Blog

|

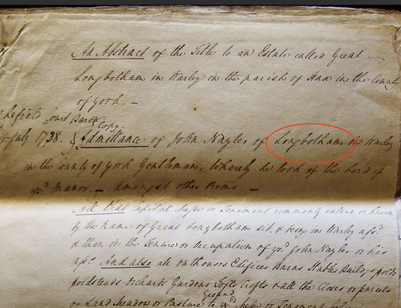

I have been interested in house names for as long as I have studied and traced house histories. They fascinate me. They can be whimsical they can be serious, historic or even descriptive. That is what I like about them. I am sure, like me, you have passed a house and wondered how it got it’s name. Here hopefully are a few pointers. Names were often chosen to make a statement about the house or the owner, perhaps to describe it’s whereabouts so every now and again they tell you something of the building’s history or clues to previous inhabitants. Of course, not everyone named their house. In fact, according to the Land Registry only about 8% of our Nation’s houses have names. Also, it should be said at the outset that we seem to have a rather ambivalent attitude towards the practice. A feeling that the Oxford English Dictionary did little to assuage, when it provided as an example of the word naff “to name your house “Gables” or “Mon Repos.”  Goodwood House the home of the Duke of Richmond Goodwood House the home of the Duke of Richmond It seems we accept that the homes of our landed gentry should bear a name. - Arundell House, the seat of the Earl of Arundel or Leicester House built by the Dudley family who were Earls of Leicester for instance, but many of us consider the naming of our suburban residences a little tacky. Yet according to Laura Wright in her wonderful book “Sunnyside,” people have named their homes for as long as there have been dwellings and examples go back to earliest English literature with the Meadhall in the epic poem Bewulf named Heorot. Throughout time we can find the use of Haw, Seld, Hallhouse and Bury frequently used with la Bordhawe, Brantefeldesselde, Ceolmundshaw as examples.  Longbottom A house in a deed dated c 1738 Longbottom A house in a deed dated c 1738 A rich source of house names can be found in medieval deeds and wills many of them describing the householder, their occupation and the appearance of the house. La fforge (1357), leCrokedhous (1335) Gladewyneshouse in Thamysestret (1328) A certain Katherine was bequeathed a tenement in 1313 intriguingly named la Hole and her brother Reginald a seld called Andovreselde in 1303. In 1290 a house named Beaurepair appeared which may be an early example of a foreign name being used on a house as there are several Beaurepairs’ villages in France. In 1285 there is reference to the rent of a tenement called Litelcaponhors as well as the “tenement “wherein she dwells”, called le Meire. In Wood Street Oxford can be found Blacke Hall formerly owned by wood seller Michael ‘de Wodestrate in 1160 which by 1361 was Blackhalle. Malsuppine in Shoreham, Sussex was sold in 1346 as a tenement which underwent many changes until 1703 since when it has been recorded as Marlipins. A deed of 1414 mentions The Old Barge, a stone and timber house named after the barges on the river nearby. Still to be found are The Jews House in Lincoln dating from around 1150 and the 12th century Music House in Norwich. In London in the 17th Century boundaries of some wards were described by the names of the houses in the streets – rather like a census enumerator’s log much later, as in “from a cook’s house called The Sign of King David…. into Huntington House…… “  Batemans in East Sussex Batemans in East Sussex Naming continued throughout the ages with many inspired by heraldry, crests, religious overtones, travel, occupations and the appearance of the building or the surrounding geographical features. Early house names were often identified by location – “a dwelling house by the orchard” or by a name associated with the owner. Batemans in Burwash built in 1634 for Mr Bateman the owner of a local forge and later bought by Rudyard Kipling is an example. Less grand names can be found in leases such as William’s Tenement or Bassey’s Cottage. Cockspur is a 16th century cottage thought to have been a venue for cockfighting. Whereas in Watchet, Somerset it is believed that fisherman used to set traps for fish in the river immediately outside Trap Hole Cottage. Atkins Living is on land owned and worked in the Middle Ages by the Atkins family Lots of names described the location or terrain such as Highlands or Broadlands or sometimes names are based upon the style or features of the house itself. Gables, Gable End, Six Gables or more often Chimneys, Tall Chimneys or even the Scottish Lum Reek (which I think translates as smelly chimney). The Pillars, High Walls all reflect the architectural merits of the building. Whilst by contrast I found the Bendorbump in Hawkshead, Crooked Cottage in Whitby, and Old Bent House near Rochdale, which all point to less successful architectural achievements.  As the urban sprawl developed, old field names vanished but armed with tithe maps it is possible sometimes to find clues in house names such as Ropers, built on the site of Ropers Shaw, Burrows Ridge and Bishops Croft all celebrating the former owners of the land. Sometimes it was quite common to have a name suggesting the acreage owned for instance Longacres, The Furlongs, North Hide (hide was a term that used to refer to 120 acres) or Spencers acre which combines the size and ownership of the field. On the subject of acreage someone suggested a rather wealthy dentist lived at Toothacrers but I have not seen that. Houses named after former occupations are many, as in Blacksmiths Cottage, Spindles a spinners cottage or Cordwainersand Cobblers pointing to former shoemakers. Where a farm or rural commercial building are converted to modern homes clues remain, as in The Coach House, Stables End and The Old Barn. Of course, Glebe Cottage, The Rectory, Manse or Priory Housel usually indicate that the land was once owned by the church, whilst Brewers and names such as The Old Plough all point to homes that have been converted from redundant hostelries. Witch Post Cottage is found in Yorkshire where builders would place the cross of Saint Andrew on the fireplace post or lintel to prevent witches flying down the chimney and entering the house to do mischief. Some names are just down right clever. Joyce Mills refers to Divyend a converted co-op store and Expo formerly a post office as examples. Obviously, the principal reason for naming a house is a means of identifying it, although of course in earlier times they didn’t always need identifying. That is as long as you were local. A house near Crowborough, East Sussex in 1780 was named The Cottage. Sixty or so years later when the census came along it didn’t even need a name as it was sufficient to identify it as Hobbs, Crowborough, Hobbs being the occupant and living at that time in one of only 20 dwellings in the village. Everyone new Hobbs. Fast forward to today and now the village is swallowed up by a much bigger urban sprawl and The Cottage has combined it’s name to Hobbs Cottage which it received around 1920, showing how house names can sometimes provide links to the house’s history As towns grew there was a need to be able to identify streets of houses, so in 1765 a numbering system was introduced in which typically houses on the left going out of town centre were given odd numbers and, on the right, even. Whilst a large number of the new crescents, terraces and squares were now numbered - house names were being added too and some of the grander homes built for the new middle classes were named after aristocracy – Montague Lodge, Sussex Villa, Somerset House etc. However, another even greater and lasting transformation was about to occur which was going to have an effect on our towns and villages as well as the naming of properties. The arrival of the railway. When the railway arrived in the 1840s villages and townships grew, often ad hoc, around the station and it was difficult to number the homes sequentially so house names were employed. Even where streets in the new suburbs were formed, they were often given house names because numbering was not possible until the whole street was finished and that often got delayed because of land ownership issues as well as the builders’ timetables.  This growth gave housebuilders an opportunity to use their imagination when trying to capture the Victorian prospective home owner and a new category of house names came into being – the hybrid. Rural idyllic place names were merged with local nature to get Ferncroft, Ferndale, Elmdene and Roselea, all of which were designed to make the new suburbanite feel that he had not strayed far from his rural roots. Thus, we find - not surprisingly - the house names in these growing towns were not that different from the villages that the occupants had left behind, although there were a few notable changes in the terminology used. The name “lodge” for instance was no longer a gatehouse at the entrance to an estate, but a gentlemen’s residence. Whilst “cottage” ceased to be associated with a small rural worker’s home, but was now a substantial property. Other changes can be noted too such as Villa became substituted by -ville to producing names like Woodville and Roseville. So as urban development continued up to and after the wars so did the plethora of house names. Some house names derive from interesting combinations. A medley of place or personal names were described by Joyce Miles in her book “Owls Hoot - How people name their houses” and she mentions Mr Mrs Bird living in The Nest, The Wildes family who chose Goose Chase; The Foxes at Reynard, the Redheads who live at Coppernobs and Mr Mrs Gammon whose house was named Rashers. All true. So that was a quick and mostly light hearted run through the history of house names. Sadly, I think there has been very little in depth study of the subject. Yet, whilst some names can be frivolous or based upon an emotional tie to the building some can provide a signpost to the house, its occupants history or indeed help us understand more about social and local history. The books or studies I have discovered are listed here- Books

Sunnyside – A History of British House Names by Laura Wright, Published by Oxford University Press Web link **Recommended read House Names Around the World by Joyce C Miles Published by David & Charles 1972 Owls Hoot – how people name their houses by Joyce Miles Published by John Murry 2000 Study House Style: the politics, conventions and practices of house -naming in 19th century Cheltenham by John Simpson British Society for Local History 2019. **Recommended read Local place names in Medieval Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 129 (2011), 155–196 Web link Papers /BlogsThe Significance of House Names to Family History by Judith Bachelor Web link **Recommended read How house names tell the story of centuries of social change in Britain by Dr Laura Wright. British Academy Monograph Web link Useful Resources Medieval Manors and their records. Web link What’s in a house name – Bristol Web Link Historical gazetteer of London before the great fire By D J Keene and Vanessa Harding. Originally published by Centre for Metropolitan History, London, 1987.British History Online Web link A- Z Edwardian London preface/introduction The 20 most popular house names in the UK Article in House Beautiful Magazine Web Link

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Trace my HouseOccasional blog with hints and tips to help you trace the history of your house and its occupants.and a general review of the world of house historians Archives

June 2024

CategoriesRecent Posts |

The HouseLand Registry

Maps Manorial Records Other Records Postcards & Photos Enclosures Books & House histories Church & Parish Records |

The People |

|

OUR ADVERTISING POLICY - This website receives no funding or any other form of award and is run voluntarily to provide information to those who want to trace the history of their house. We would like to say thank you to all those who have or will in future click on the advertisements they find on this page. We know they can be a nuisance or distraction and we try to make sure that they are relevant to the information we provide and our readers. However the modest income we receive from them keep the web site going. So thank you.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed